What Device Makers Need To Know About Design Verification and Validation

Design verification and validation are two essential steps in medical device product development. It’s easy to confuse the two, but there’s a simple way to remember them:

-

Design verification answers the question: Did we design the device right?

-

Design validation answers the question: Did we design the right device?

With that distinction in mind, let’s take a closer look at both design verification and design validation, and how you can successfully execute both during product development.

What do design verification and validation mean in medical device product development?

You can find the FDA’s definitions for both design validation and verification in 21 CFR Part 820.3.

What is design validation?

FDA defines design validation as “establishing by objective evidence that device specifications conform with user needs and intended use(s).”

In the FDA’s waterfall diagram of design controls, you can see that the process begins with determining the user needs for your device.

So, if one of your user needs is that the device “must be capable of one-handed operation,” part of design validation will be establishing through objective evidence that you’ve built a device which can be wielded with one hand. In other words, did you design the right device?

NOTE: When you hear someone refer to “validation,” it’s a good idea to ask them what type of validation they’re referring to, specifically. In the medical device industry, they could be referring to software validation, process validation, or design validation. In this post, we’re only talking about design validation.

What is design verification?

FDA defines design verification as “confirmation by examination and provision of objective evidence that specified requirements have been fulfilled.”

In other words, your design verification is about ensuring that your design outputs meet your design inputs. FDA defines design inputs in 21 CFR 820.30(f) as, “the physical and performance requirements of a device that are used as a basis for device design.”

This is one of the reasons design validation and verification are easy to mix up. Your design inputs—those physical and performance requirements—are derived from your user needs. Earlier I used the example of a user need for which a device must be capable of one-handed operation.

From that user need, you might create design inputs related to size, weight, texture, and ergonomics. For instance, “The device shall have a maximum weight of two kilograms.”

Using methods like testing, inspection, and analysis, you will then verify that your design outputs meet your design inputs. Does the device weigh two kilograms or less? Did you design the device right?

What are best practices for design verification and validation?

Design verification and validation both require some foresight, and it’s essential that you create plans for each of them ahead of time. Proper preparation will help you discover and avoid potential obstacles early in the process and improve your efficiency.

Tips for successful design verification

Your design inputs are the foundation of your design verification. There is an art to writing design inputs, and the way you go about it will be a major factor in how effective your verification process is.

So, focus on making your design inputs as clear, discrete, and actionable as possible. Ambiguity leads to mistakes or difficulty in verifying if your outputs have met your inputs. If your inputs aren’t testable, then you need to break them down or rewrite them in such a way that you’ll be able to verify them later on.

Finally, start planning your design verification early. You can start thinking about how you’ll verify your design inputs as soon as you’ve defined them, and you may even be able to develop some of the tests you’ll use during product development.

Tips for successful design validation

The most important thing you need to know about the design validation process is that it has to include actual production units, and they need to be tested under the specific, intended environmental conditions. You should also have intended end users of the device test it during these validation tests. The goal is to ensure it works as they need it to, under the conditions they need it to.

As with design inputs, be sure that your user needs are clearly defined at the beginning of the design and development process. Vague language will come back to haunt you. For example, if one of the user needs is that “the device needs to be safe,” how will you validate that? Using what definition of safe? Safe compared to what? Be specific with your user needs and avoid vague or relative language.

Finally, don’t forget that design validation must include packaging and labeling, too. These are both essential aspects of ensuring the medical device can be used safely and effectively.

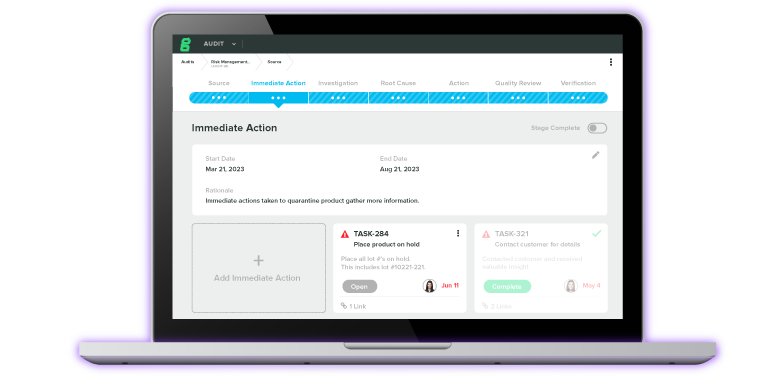

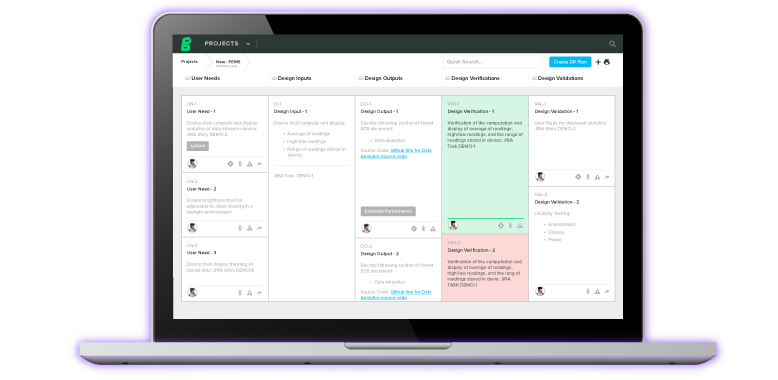

Manage all your verification and validation activities with a dedicated design control software

Planning and executing design verification and validation requires a deep understanding of the relationships between design controls. And if you’re using a paper-based QMS to keep track of all your work, it’s impossible to step back and see the full picture.

Greenlight Guru’s QMS solution features a dedicated Design Control Software workflow built specifically for medical devices. We understand the challenges of the design and development process, which is why with our software you can create detailed design control objects, link complex configurations, and attach documents with one click. Better yet, you can see it all in a single, enhanced view.

So, if you’re ready to visualize the connections within your device’s design and your QMS like never before, then get your free demo of Greenlight Guru today.

Bonus Podcast Episode about Design Verification & Validation

Here’s a question for our listeners: When it comes to making sure your medical devices are safe and effective, is it more important to find the right answers or to ask the right questions?

In this episode of the Global Medical Device podcast, we delve into everything related to design verification and validation, which is often called V&V.

We talk to a familiar guest and medical device expert Michael Drues Ph.D., president of Vascular Sciences. Michael works for and consults with medical device companies located all over the world. He also works with the US FDA, Canada Health, and other regulatory and government agencies in the US, Canada, Europe and elsewhere in the world.

Listen as we discuss why V&V is so important, the major differences between verification and validation, how they fit into your approval process and more.

Listen now:

Like this episode? Subscribe today on iTunes or Spotify.

Some highlights of this episode include:

-

Validation and verification: What do these two words mean, what are the major differences between the two, and how do they both fit into your approval processes?

-

How to know when you need to go to the FDA with a 510k form and when you can simply use a letter-to-file.

-

The importance of knowing why you’re running the V&V tests to begin with.

-

How you can use the Five Whys tool in your V&V process.

-

Why it might not make sense to go through the V&V process, and how to approach the FDA to come up with a different procedure to satisfy the regulatory requirements.

-

Advice on which questions to ask the FDA during the pre-submission process with the FDA.

Additional Links and Resources:

Medical Device Design Controls: Following The Regulation Vs. Understanding Its Intent

Best Practices for Medical Device Change Management

Information About the Five Whys

The Beginner’s Guide to Design Verification and Design Validation

Memorable quotes by Mike Drues:

"We need to focus on asking the right questions. V&V is all about demonstrating what’s safe and effective.”

"When working with the FDA, tell, don’t ask. Lead, don’t follow."

Transcription:

Announcer: Welcome to the Global Medical Device podcast, where today's brightest minds in the medical device industry go to get their most useful and actionable insider knowledge, direct from some of the world's leading medical device experts and companies.

Jon Speer: Medical device product developers, let me start today's episode with two questions. Do you want the right answers, or are you more interested in asking the right questions? Think about that for a second or two. Yes, these questions are important, and they really are the essence of verification and validation. On today's episode of The Global Medical Device podcast, I once again talk with Mike Drues. Mike is with Vascular Sciences. He consults with medical device companies all over the world, with FDA, Health Canada, and other regulatory bodies as well.

Jon Speer: And today, he and I dive into some depth and detail on verification and validation. Process, designs, software, yeah, all of the above. We explore how these topics are important to making sure that your medical devices are safe and effective. So be sure to listen to this episode of the Global Medical Device podcast.

Jon Speer: Hello, and welcome to the Global Medical Device podcast. This is your host as always, and the founder and VP of Quality and Regulatory at greenlight.guru. Today, we have a topic that... Well, if you're in the medical device industry, and you're bringing new products to the market, this is a topic that applies to you. The topic, broadly speaking, is design verification and design validation. Today, Mike Drues and I, Mike with Vascular Sciences, he consults with medical device companies, FDA, and Health Canada. Today, Mike and I are going to dive into the differences between verification and validation, and why that matters. Mike, once again, welcome to the Global Medical Device podcast.

Mike Drues: Thank you, Jon. Always a pleasure to be with you and your audience. I'm really looking forward to our conversation. And Jon, just to kick things off, one of the common questions that I get, and I'm sure that you get it as well, is, we use this phrase "verification and validation", or in the vernacular "V&V", but what exactly does that mean, and what's the difference between the two?

Jon Speer: Right. Right, yeah, it's a great question, and I always... Whenever I'm asked that question, I have to ask the person's context, because as you said or hinted at, maybe V&V or verification and validation, those terms are used in a lot of different capacities. So I always ask the person, "Can you give me the adjective that you're referring to? Are you talking about process? Are you talking about software? Are you talking about design? Because that adjective is very, very applicable to the impact that V&V has on whatever your question might be." But in the context of design, verification and design validation, that's very much a design control topic. And those actions mean something completely different.

Jon Speer: And, Mike, this is... I don't know if you remember how you and I kind of first met, but [chuckle] you wrote a blog post, actually, this kind of comes full circle for us a little bit today, but you wrote a blog post on, I don't remember the entire topic, but it did dive into verification and validation. It talked about design verification being proof or evidence that you designed the product correctly, and design validation about making sure that you designed the correct product.

Mike Drues: That's correct, Jon. The difference between getting the right answer versus asking the right question. And I personally believe, and you're exactly right, you and I have talked about this many times in the past, I personally believe that the focus should not be on getting the right answer, but rather are we asking the right question. And whether we do that in the context of verification and validation, or design controls, or something else, it really doesn't matter. But you, in your comment a moment ago, Jon, you sort of differentiated... It depends on what your context is. In other words, the manufacturing process, the design, the software. And I would agree with you in the sense that the details of how you carry out the V&V under those different situations might differ, but fundamentally, isn't the idea, the whole reason why we're doing the V&V itself, whether it's a manufacturing process, or a design, or a software, is it fundamentally, isn't it the same thing?

Jon Speer: I guess I never really thought about it in that context before, Mike. I always thought that that adjective was the differentiating factor. But, as you asked that question, it really got the gears turning. And I think fundamentally, you're correct. Verification is about demonstrating that your outputs, and for those of you who can't... [chuckle] Obviously, this is an audio podcast, not a video, but I used air quotes. But the outputs, verification is about proving that the outputs meet your inputs. And it doesn't matter if it's a design, control process, or a manufacturing process, or a software process, there are inputs and outputs, and verification is about demonstrating that those things have, in fact, met one another. And then, to go from a validation standpoint, validation is about demonstrating that the total output of whether it's design, or manufacturing, or software, or whatever the case may be, it's about demonstrating that that total output meets what you wanted it to do to begin with. Why you did that, why you started the design control process, or why you started your manufacturing, or why you started your software. So the validation is the proof or evidence that it meets those needs.

Mike Drues: I agree with you, Jon. And to help our audience understand, let me give an example, and I would love to hear your thoughts on how you approach this as well. But this is from the area of change management. And I did a column on this a few months ago. One of the most common questions that I get from medical device designers is, "If I want to make a change to my particular medical device, let's say that this device is already on the market, and for the sake of discussion, let's say it's a 510(k) device, if I want to make a change to this device, it could be a design change, it could be a manufacturing change, it could be a material change, it could be lots of different things. If I want to make a change to this device, how do I know if I need to go to FDA to tell them about this in the form of a special 510(k), or on the PMA side of the world of PMA supplement, versus if it's not a significant enough change, then I can handle that information internally doing what we call a letter to file?"

Mike Drues: And this is one of the most common questions that I get. It's also one of the things that generates probably more problems for medical device companies than probably any other single thing. And again, I don't want to get too far into the details of how we handle that, but simply put, it comes down to the verification and validation. In other words, you need to demonstrate, first to yourself, to your own organization, that that change, whatever it is, will not affect the safety, efficacy, performance, and so on and so on of the device. That's not something that you can just decide willy-nilly. You need to do a little bit of thinking, you need to do a little bit of investigation, maybe in terms of a literature search, you need to do maybe a little bit of bench top testing. I'm not talking about turning this into a PhD dissertation, but you need to do a little bit of work in order to convince yourself of that.

Mike Drues: And to me, fundamentally, that's the V&V, that's the whole essence of it. I don't know, Jon, if you've ever thought about it that way, or if you have similar experiences when companies come to you and say, "Hey, Jon, we want to change our device. What exactly do we need to do?" I personally believe we should begin with the engineering and biology, and not with the regulation. But that's my approach, Jon, what do you think?

Jon Speer: Well, I think that's... I generally agree with some of that, but I think to try to make a decision without a regulatory context, obviously, eventually you're going to have to cross that path too. So a lot of the customers that I work with and advise, I want them to do factor that regulatory piece as part of their decision making process. Now, don't mishear me, they should not be making decisions only because the regulation said so, they should be doing what makes good, as you've said before, prudent engineering sense, and they should make sure that the devices that they're developing and putting into the marketplace are safe and effective. And I think that V&V is all about demonstrating safe and effective, safe and effective.

Jon Speer: But doing so on a regulatory context is important, because a lot of companies that I work with, they get their product through the design control process, they get it through their submission, and then they launch into production, and to assume that you're going to launch a product into production and never make a change, is very naive. There are infinite reasons for why you will change your product, and it could be as simple as changing a logo on a label, to as complex as having to change the entire materials that are involved in that. And for any of those changes, I try to drive my customer, the companies that I work with, I try to drive them towards understanding the impact of that change. And I think there is a lot of confusion about V&V, making sure that you've conducted the necessary V&V activities before you actually implement that change. And I think another piece of that that you can't ignore is regulatory impact.

Mike Drues: Well, I agree with you, Jon. And let me just clarify, 'cause I don't want to be misunderstood here. When I say that we should not begin with the regulation, that's not to imply that the regulation is not important, that's not to imply that we do not need to follow the rules. On the contrary, rules are important. I'm not trying to advocate anarchy here. [chuckle] But what I'm simply suggesting is, we need to do what makes sense. And we need to first understand from an engineering and a biology perspective what makes sense, and then we need to bring the regulation into it. I was in a situation, not long ago, where somebody came to me, this was a V&V kind of a question, they were designing a test methodology, and they wanted my help to make sure that it met the design control in the V&V requirements. And I said, "Sure, I'd be more than happy to help you do that, but first let me ask you a question, why are you doing this test?" He had no idea.

Jon Speer: Right, right.

Mike Drues: Absolutely no idea. Now to me, again, I'm not always, as my wife would say, the brightest bulb on the tree, but to me, what's the point of trying to understand what the V&V requirements are to design a test, when you don't even know why you're doing the test to begin with?

Jon Speer: Yeah, and that, Mike, is the essence, I think, of this. Because I totally every day talk to people, and they're going through the motions. And they almost just blindly are following down this path or going down this path of, "I need to do X, Y, and Z V&V activity, because that's what I need to put in my submission." [chuckle] In your question as to why. An interesting story on my end, we recently went through an audit, not related to V&V, but an ISO audit, and the ISO auditor was saying, "Hey, we need to do a better job of root causes." And he's like, "Here's a tool that I recommend, it's called 'The 5 Whys'." And the 5 Whys tool, I'm sure you've used that before, or probably heard of that. Or if not, you have children, and you can probably remember it to when those children were a lot younger, like three, four, or five, and they keep asking you the question, "Why? Why? Why?" And that's the same context of this tool. But it could be very, very useful in a lot of applications, including things like verification and validation. If I am doing a test, I should be asking myself, "Why? Why? Why?" And I should keep asking myself "Why?" until I get to that root cause and understand. And if my answer, my root cause is just to satisfy a regulatory obligation, then I probably need to rethink my approach.

Mike Drues: I could not agree with you more, Jon. I've been in many situations, and I'm sure you have as well, where I'll be inside of a medical device company, and they'll be doing tests. It could be bench top test, it could be animal test, clinical, whatever. And I ask, "Why are you doing this test?" And they either, A, they'll say they don't know, or even worse, they'll say because it's required. And I would say, "Okay, but if it was not required by FDA or somebody else, would you do the test?" They say, "No." "Does the test provide any value?" They say, "No." To me, doing something for no other reason than it's being required is not a very good justification for doing it.

Mike Drues: Now again, let me be crystal clear, I'm not advocating anarchy, I'm not saying that rules are not important. But in those situations, I will go to FDA, and I will go to them prophylactically, "I will not do this in my submission." I will go to them prophylactically in a pre-sub or something like that and say, "Here's what the regulation says, here's what the guidance says. But in our particular case, it's not appropriate, or perhaps it's not possible, and here's why. And here's what makes sense to do instead." And by the way, I see a lot of companies, they do that, but they do that in the regulatory submission, in the 510(k) or the de novo or whatever it is. In my opinion, although the regulation doesn't prevent you from doing that, that increases your regulatory risk tremendously. You're just about guaranteeing yourself a kick back on your submission.

Jon Speer: Yeah, and that's pretty late in the process, too. If I'm waiting to get some sort of... Or if I'm making a lot of assumptions on V&V, and basically hoping and crossing my finger that by doing so in a de novo or 510(k), that's pretty late in the process. I like the suggestion that you have of getting some feedback from FDA or a regulatory body much, much earlier in the process, through the pre-sub program. And if you're outside the US, you can certainly talk to notified bodies about that long before you put together that official submission.

Mike Drues: I agree, you and I are very much singing the same song on this, Jon. There is nobody that's a bigger fan of communication with FDA or any regulatory agency than I am. I will communicate much more frequently than any regulation ever requires me to communicate. But there's a caveat to that. One of my mantras in regulatory, as you know, has become, "Tell, don't ask. Lead, don't follow." It amazes me how many people literally walk in to FDA and ask FDA, "What do I do?" [laughter]

Jon Speer: Yeah, like the FDA is their consultant, right?

Mike Drues: That's exactly right. And in my opinion, that's a terrible strategy for a couple of reasons. First of all, it's not FDA's job to tell us what to do, it's our job to know what to do. That's number one, and to sell it to FDA. But second is, when you ask that question at FDA, you're opening up a Pandora's box, and you have absolutely no idea what you're going to get in return.

Jon Speer: Careful what you ask for, right?

Mike Drues: Exactly right. So I spend a lot of my time actually helping companies prepare for pre-subs and actually doing pre-subs. I'm down now doing pre-subs at FDA pretty much once a month, if not even a little bit more. So there's no bigger fan of communication with the agency than I am. But remember that caveat, "Tell, don't ask. Lead, don't follow." "Here's what makes sense, and here's why it makes sense." And by the way, I don't even end my presentations at FDA by asking, "Are there any questions?" because, believe me, if there are reviewers in the room, and if they have questions, they will ask them, that's their job.

Jon Speer: Yeah, yeah, yeah. That's essentially, because if you look at the guidelines for a pre-submission, and I know we're maybe on a slight tangent, we'll bring it back to V&V here in a moment, but there is that section on the expectation on a pre-sub that you list all the questions that you want to know from FDA. And I just reviewed a pre-sub from someone the other day, and they had a long list of questions, and my comment to them was, "Expect an answer for every question that you ask, and realize that you may not like some of the answers that you get. And although the account or the response from the FDA in your pre-sub may be non-binding by the agency, expect that if they provide you some guidance or direction or recommendation on the things that you should do, you can bet quite a bit that they're going to be looking for that when it comes time for you to put together that formal submission."

Mike Drues: Well, you're right, Jon, and you may not have realized it, but you've just hit on one of the things that causes my blood pressure to go up higher than almost anything else. [laughter] One of the very few...

Jon Speer: You seem so calm today. [laughter]

Mike Drues: I try. One of the very few requirements of the pre-sub request, it's actually, it's a very simple thing to request a pre-submission meeting with the FDA, but one of the three requirements, as you just described, is we have to submit our questions to FDA in advance. And to me, this violates one of my most basic rules, and that is, never, ever, ever, ever ask FDA a question. [laughter] And so I personally, perhaps I shouldn't say this in a recorded podcast, I personally find it condescending of FDA to insist that I have to ask them questions. But here's the problem, in order to qualify, in order to get the meeting scheduled, in order to jump through that regulatory hoop, we have to give them some questions. So here's my advice, and I do think that we should talk about this in more detail.

Jon Speer: I'm getting on the edge of my seat, by the way, Mike, 'cause this seems like this is very helpful.

Mike Drues: Yes, but here's my advice, when we craft those questions... We did another podcast where I talked about designing your labeling, for example, designing your indication for use statements by doing a lot of wordsmithing and so on and so on. I take exactly the same approach. I design those questions, such that I create what my attorney friends call leading questions, and that is, in coming to an answer to that question, they can only answer it... Sorry, they can only answer the question. We create a leading...

Jon Speer: It's that blood pressure thing, right? [laughter] I guess it's up a little bit.

Mike Drues: Yeah, thank you. We design these leading questions so that the only answer they can come to is the answer that we want them to come to. This is why the attorneys call it a leading question. So the unfortunate reality, the way the pre-sub process has been created, and philosophically I love the pre-sub process, but I just have a real problem with this one requirement. In order to get the meeting scheduled, you have to submit questions to FDA, and so be very careful. And you described this a moment ago, you ask your questions, but you might not get the answers that you want. Be very careful how you phrase them.

Jon Speer: Yeah, to say it another way, Mike, so what you're saying is, ask the question in a way that gives me the answer that I want.

Mike Drues: Bingo, that's exactly right. Thank you, Jon. You said it much simpler than I did, but that's exactly right.

Jon Speer: Well, you've been through this, like you said, you're down at FDA dealing with pre-subs month after month after month, and so you've got a lot of that experience. So alright, let's bring the topic back to the V&V topic that we started with. Although we've been really dancing around and all of this does apply, but I want to share a short story about a startup company, and it is a V&V related story. And they're early stage, but they're all about this First-In-Man, FIM. They've even crafted an acronym about this, First-In-Man, First-In-Man.

Mike Drues: Is that a politically un-correct phrase nowadays, Jon?

Jon Speer: I don't know, I'm not going to touch that. [laughter] But they're all about getting their device used on humans basically, right, and they've been going down this path of animal study, after animal study, after animal study, and scouring the globe to figure out where they can establish a protocol and actually build units and go to that country, wherever it might be. And even if it's a country that we didn't even know was on the globe, they're going there to use their product in a First-In-Man study. That's what's motivating them. And I'm thinking to myself, "Wow, there's so much more from a V&V perspective that is important, that you could probably demonstrate before focusing on that First-In-Man. So I'll stop there, I'll get your comments about that.

Mike Drues: Well, I think that's a good point, Jon, and I'll share a similar experience from my world, and tying the V&V into the regulatory a little bit more, in some of the early First-In-Man or First-In-Human kind of studies. And that is, in low risk, in what we call non-significant risk or NSR kinds of devices, because as you and your audience probably know, if you're working on an NSR device, you do not need an IDE, that is, you do not need FDA's "permission" to begin your clinical study. You only need the permission of the Institutional Review Boards or the IRBs. And in an NSR study, the V&V becomes even more important, because the FDA is not going to be looking at it before it goes into the people. Therefore, the only people that are going to be looking at it is the IRB. And in that sense, the IRB, if they're doing their job, and let's be honest, sometimes they do, sometimes they don't. If they're doing their job, they should be asking many of the kinds of questions about biocompatibility, about liver ability, about ergonomics, all those kinds of things, that they normally would not ask about, because the FDA would ask about them. But because it's NSR, because there's no IDE, the FDA does not get involved.

Mike Drues: Now, one other thing, and I'll let you add on to this, Jon, I still, in those situations... We talked about pre-subs a moment ago. I still go to FDA in advance, and I say, "Listen, as a matter of professional courtesy, we don't have to come to you, we're not coming to you and asking your permission, but as a matter of professional courtesy, we want to let you know here's our device, here's the way it works, here's what we're saying about it, here's the clinical trial that we're starting. It is non-significant risk, and here are all the reasons why." I just put all those cards on the table, just to make sure that everybody sees it the way I do, just to make sure that we don't have a problem later on. But coming back to the V&V piece, if you're working on a 510(k) device that does require a clinical data, and it is a NSR device, keep in mind, that FDA, although according to the regulation, does not have to be involved formally, it's only the IRB. The IRB is probably going to be asking you those V&V kinds of questions. And taking it a step further, my suggestion is, consider taking it to the FDA anyway, even though you're not required to, just to make sure that everything passes the sniff test. Anything you want to add to that, Jon?

Jon Speer: Well, maybe a slight twist. A company developing a new device, they always seem very interested in getting that clinical actual use experience. And I would say, the other thing that I always find intriguing is, a company who is very, very early, they basically just have one prototype or maybe a couple of prototypes, and they're going to go down this NSR path, even before they've really fully designed their product. They've just, excuse the expression, but hacked something together in order to get into actual use to be able to see, use that clinical use as a means to help them almost really determine what the design needs to be. And sometimes I think that that's a little backwards.

Mike Drues: I agree. Stephen Covey said, "Begin with the end in mind," and I think that's a lesson that we can apply here. Figure out where you want to be at the end of the game, and then work backwards to make sure that we end up in that right place. And it sounds like a very simple idea, and in fact, it really is, but it's amazing to me how few people actually do it.

Jon Speer: I don't remember if I've shared this story with you, and I won't do it on today's podcast, but I can very distinctly remember my first experience, clinical experience with a device that I designed and developed. I was present for the use, the first use of this particular device many, many years ago. And I can remember that whole... But I had gone through the entire design and development process, I had worked with the clinicians early on, I had had some proof of concept prototypes and concepts and so on, but I tried to cast a wide net and get their feedback and understand the clinical need that we were trying to solve, of course, and then took it through all of the V&V activities, biocompatibility, performance testing, and all of the things that went along with that. But the clinical use is obviously important for any technology. And I realize there's a marketing need in a lot of cases, and in other cases there is an actual regulatory need to be able to demonstrate that my product works. But I think sometimes companies get too hung up on that actual clinical use, and they put so much weight on animal studies and clinical studies, that they forget how to be good engineers in the process.

Mike Drues: I think there's a certain degree of truth to that, I got to give you that. I think there are pros and cons to everything, as my grandmother used to say many years ago, "That's why they make chocolate and vanilla." [chuckle] So I think there's a place for bench top testing, I think there's a place for animal and for clinical testing, obviously, and we have to recognize that no kind of test, or computational testing as well, no kind of test is going to be perfect, there's going to be limitations. And early on in my career, I spent a lot of my time, when I first started consulting for FDA, evaluating people's testing methodologies, when they came in as part of a submission. Another thing that you're hinting at, and this could be a topic of a different conversation as well, is the whole aspect of usability testing, or human factors, or ergonomics, whatever it is that you want to call it. So, Jon, I'm sure that you and I can go on talking like this forever. [laughter] I think this is fun, but your audience probably has lives, and they have other things to do. To wrap this up, what do you think is the most important thing that people should remember about V&V moving forward?

Jon Speer: Well, I think the most important thing is realize that verification specifically does not always mean a test. As an engineer, I may have a propensity or an interest or a desire to do some sort of test to get hands on, to break something, or to prove something through some sort of testing method, but sometimes verification could be much, much simpler than a test. Sometimes I can do some sort of analysis, sometimes I can do some sort of inspection, and that is more than sufficient to address my need to prove that my outputs meet my inputs.

Mike Drues: I think that's an excellent takeaway message, Jon. Thank you for sharing that. My message would be something a little bit similar, but I'm going to take this maybe to a slightly higher level. It does have V&V implications, but it has broader implications as well. One of the most common questions that I get from medical device companies across the board is, "Mike, you work for a lot of different medical device companies, you also consult for FDA in Canada and Singapore and other countries. If we came to the FDA with our new widget, with our new medical device, what do you think they would want to see in terms of safety, efficacy, performance, V&V, whatever you want to call it?" And I say to them, "Okay, I understand that's an important question to you. I understand why you're asking it. But let's look at it from a slightly different perspective. Sooner or later a family member, a friend, perhaps even ourself, is going to be on the receiving end of that medical device. When that day comes, what do we individually, what would you, Jon, as an individual need to see in terms of safety, efficacy, performance, in order to put your personal stamp of endorsement, if you will, on that device?"

Mike Drues: In other words, in order to say that that device is okay to be used in my spouse, in my child, perhaps even in myself, then and only then, should we go to FDA, or Canada, or whoever it is, and have a discussion as to doing what makes sense. Again, I think, there has become so much emphasis on simply following the regulation like a recipe. There's an adage that we use in medicine frequently, "The surgery went perfectly, but the patient died anyway." The engineering equivalent of that is, "We designed the medical device perfectly, but the patient died anyway." The regulatory equivalent of that is, "We followed the regulation perfectly, we did all that FDA asked us to do, and yet the patient died anyway." These things actually happen more often than some people might think, and the only solution to mitigate or hopefully eliminate that, is to get people to think. And that's not something that is so easy to do. So that's my takeaway message. Yes, it applies to V&V, but it applies more broadly than that as well.

Jon Speer: Right. So Mike, as you mentioned, we have a good time on these podcasts, and we can certainly go on and on and on, and maybe we can put together a whole unabridged series of books on the topic that we can have people download and listen to on their drive to work, but today we're going to wrap that up. And again, you can find Mike Drues. Mike is a prolific author, and speaker, and consultant, when it comes to medical device industry, and FDA, and Health Canada. Look him up, look up Vascular Sciences, Mike Drues. D-R-U-E-S. He's all over LinkedIn, he's all over the internet. Just do a quick search, and you'll find some wonderful information that Mike shares with the industry. This has been Jon Speer, the founder and VP of Quality and Regulatory at greenlight.guru, and this has been another exciting episode of The Global Medical Device Podcast.

About the Global Medical Device Podcast:

![medical_device_podcast]()

The Global Medical Device Podcast powered by Greenlight Guru is where today's brightest minds in the medical device industry go to get their most useful and actionable insider knowledge, direct from some of the world's leading medical device experts and companies.

Like this episode? Subscribe today on iTunes or SoundCloud.

Etienne Nichols is a Medical Device Guru and Mechanical Engineer who loves learning and teaching how systems work together. He has both manufacturing and product development experience, even aiding in the development of combination drug-delivery devices, from startup to Fortune 500 companies and holds a Project...

Related Posts

Design Validation vs. Human Factors Validation

Design Assurance: The Unsung Heroes of R&D

Why Design Verification Matters in Medical Device Design and Development

Get your free PDF

The Beginner's Guide to Design Verification and Design Validation for Medical Devices

%20Design%20Verification%20%26%20Validation.png?width=1700&name=(cover)%20Design%20Verification%20%26%20Validation.png)